How I Bought and Estimated the Purity of Sodium Dichloroacetate

By early June I'd finished chemoradiotherapy to stop further growth of a terminal brain cancer. There was a scheduled six-week pause to "give my body a break," but the main questions on my mind were whether or not to take that break and if not, what to do instead. I had no interest in giving the thing that was still left in my brain breathing room, so I looked into treatments that a person with training but limited resources could try.

Using what I'd learned as a chemist both for my PhD and in big pharma, I looked for leads and found one, dichloroacetate, ("DCA," "sodium dichloroacetate"). The form of this material most commonly used is sodium dichloroacetate, but I'll use the two terms interchangeably.

I remember asking Dr. Neuro-oncologist about starting on DCA. "I can't prescribe that to you," they told me. Despite the administration of DCA to humans for years in a variety of investigational contexts, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has not approved DCA for any use. Dr. Neuro-Oncologist's response wasn't unexpected, although I had hoped that compassionate use would apply. That "can't" may actually be a "won't" but I'm not sure. Either way I'd have to find my own DCA.

But I was left with a glimmer of hope. "I can continue to monitor you," Dr. Neuro-Oncologist told me. This meant both blood labs and MRIs. It was more than I'd expected. It meant that if something were to go seriously wrong, there'd be an early warning system.

To be clear, I believed that the most likely outcome of self-administering DCA would be nothing. There would be no hinderance of the regrown tumor that was now plowing through my brain, no improvement of my symptoms, and no time added to my life. Even so, the literature I'd read presented multiple lines of evidence for a positive effect on glioblastoma progression.

Beyond lack of effect, my main concern was that I'd get my hands on a batch of something that either wasn't DCA, or was so badly adulterated that it would leave me wishing I'd never tried this desperate idea. Nor was this just theoretical. In 2010 the US Department of Justice convicted a Canadian man for selling "a white powdery substance that was later determined through laboratory tests to contain starch, dextrin, dextrose or lactose" as DCA over the internet. Next time it may not be a carbohydrate mixture that gets delivered but something more lethal. But even if powdered sugar were delivered, the net effect on me could be the same as lead acetate.

There were risks, but every option had them. And they were all hard to quantify.

The first problem was getting my hands on material. This could be broken into two parts: (1) sourcing; and (2) purity determination.

Buying DCA from a source I trusted was about as difficult as I thought it would be. Chemical companies like Aldrich and TCI want nothing to do with randos like me, for understandable reasons. I'd bought lots of chemicals from these companies and others while working as a medicinal chemist in big pharma, but that door had slammed shut long ago.

That left only the smaller operations. As I expected there were plenty on Amazon. I placed an order, using the same sequence of clicks I'd used the last time I bought socks. A few days later a bottle from a company called "DCA Labs" arrived by mail.

That left problem two. This may seem like no problem at all. Just look at the official certificate of authenticity included with the bottle. Easy.

I immediately tossed that certificate in the trash. Of course this company says it's pure. Why wouldn't they?

I knew from doing this kind of thing many times before that I had a few options, including: melting point and NMR spectroscopy.

My hopes for melting point were high. Using a simple device and a few specks of material, I would determine the melting point of the powder I'd been sent. It should be sharp (a 1 °C range) and should match a previously-reported value (ideally more than one).

But I hit two problems I couldn't work around. The first is cost. Melting point apparatuses, although simple, are not cheap. The one I wanted ran well into the thousands of dollars. There are much cheaper options, but they looked really cheap. Second, sodium dichloroacetate was reported to melt with decomposition. Apparently, it reacted on heating, resulting in melting points unsuitable for the technique I had in mind. I'd also noticed that not only was my material extremely water soluble, but also quite hygroscopic. It would take just a little to throw off the entire measurement. Even if I could avoid decomposition, I'd still get a range due to variable hydration.

The second option, NMR spectroscopy, would be my first choice but I knew this kind of instrument was ridiculously expensive. Think Beverly Hills mortgage expensive. Even if you could afford that, you'd need to hire a PhD expert to set up and maintain the thing, not to mention sourcing liquified gasses. In the last several years, benchtop NMR instruments had become available, but they still ran well into the thousands of dollars. Throughout my entire career as a bench chemist I had access to all of the NMR instrumentation and support I could use. Not so now.

But while working as a medicinal chemist I did run across something that might be used now: a pay-per-sample NMR spectroscopy service. These can be found in areas with biotech hubs, typically close to large research universities. Fortunately, I lived in such a place. And even better, it had one of these labs. If I weren't so lucky, it might have been possible to send the sample by mail, but I haven't explored this.

I was interested in two nuclei: 1H and 13C. I'd use the spectra obtained from observing them to determine both identity and purity. It had technical advantages over melting point, and there'd be no startup cost. After delivering the sample in person, I had the results within a couple of business days for about $100. To date I've done this analysis on two different batches of DCA.

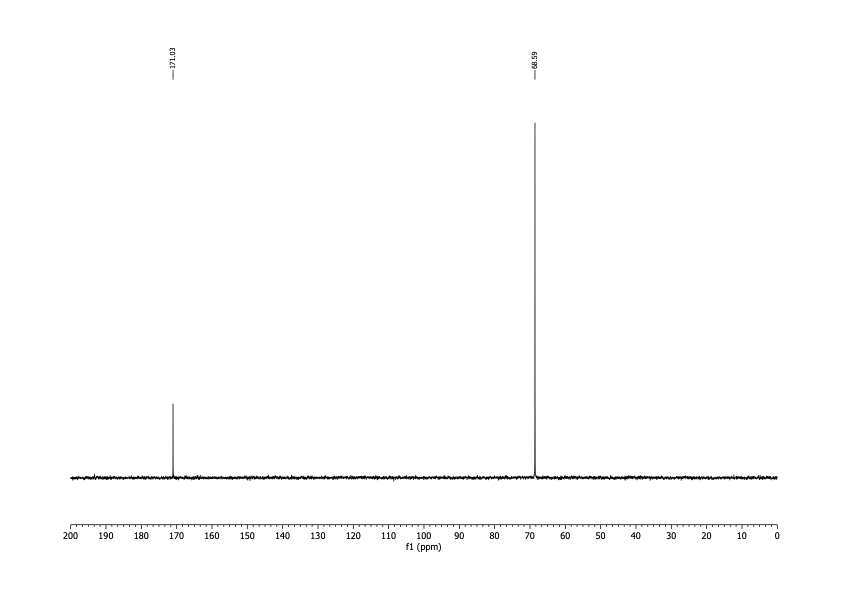

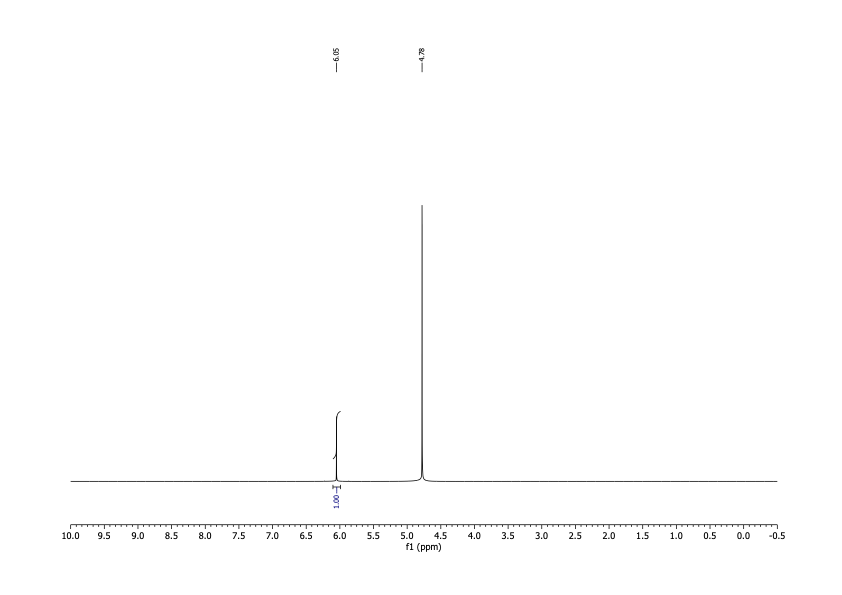

The spectra matched what I was expecting qualitatively. For the 1H spectrum there should be one peak between about 5 and 6 ppm (there would be another for water). For the 13C spectrum, there should be two peaks, one around 170 ppm and the other somewhere below 90.

It's possible to run simulations for these numbers, but I wanted literature values. Unfortunately, I was able to find none, despite the fact that multiple studies mentioned assaying the purity of DCA by NMR. I was, however, able to find values reported by a spectroscopy database supported by the Japanese government. The record I found reported both carbon (171.6 ppm, 69.35 ppm) and proton NMR (6.063 ppm) spectra.

The spectra I got matched these shifts. From the high signal-to-noise ratios I concluded that any organic contamination was present at a level of no more than 2%. That was good enough.

There is one factor my analysis doesn't account for, and that's cation (i.e., sodium). For example, what if I'd been shipped lead dichloroacetate? Elemental analysis might be an option, but my attempt came back way off. This could be explained by hydration, so I avoided drawing conclusions.

Nor was mass spectrometry helpful because the parent I was looking for was not present even as the sodium adduct in positive mode, and the negative ion parent was likewise not found. Peaks suggesting fragmentation/rearrangement of dichloroacetate were present, but for my purpose this was not enough. Given time and access to an instrument, I imagine a technique to detect in either positive or negative mode could be worked out. But even if it could, this would not address the purity problem, and it may not even fully address the cation identity problem.

Inductively-coupled plasma (ICP) or atomic absorption (AA) spectroscopy were also feasible and I'd worked in a lab many years ago doing that kind of testing — for corporate clients. I may follow up on this direction in the future, but the odds of success seem low. While writing this article, it occurred to me that a consumer-oriented water-testing facility might work, but it's not clear how many cations could be ruled out. Knowing myself, I'd only settle for all of them, and experience told me this could be a very tall order.

Ultimately, I decided that it was unlikely that a company selling a product like this, having taken all the trouble to get the organic part right would botch (or sabotage) the inorganic part. Furthermore, the sodium salt is likely the cheapest product to make by far. If you wanted to cut corners, you wouldn't do it by swapping sodium for lead, cadmium, or mercury. I wasn't very happy with this compromise because there are still scenarios where metal contamination could enter the process, but didn't see a way to solve the problem given my constraints. At least it was possible that gross mis-characterization of the counterion might show up in the proton or carbon NMR spectrum.

If I were facing a bad case of acne, I would have abandoned this crazy project long ago. But dealing with a terminal illness has a way of raising risk tolerance.