Progression

In May 2023, about two weeks before the start of chemoradiotherapy, I'd noticed increasing loss of control over my left leg, especially in the calf and foot. I sensed this in two ways. The first was during my at-home physical therapy program. Repeating the same exercises day after day for weeks on end revealed those motions that were becoming more difficult or impossible. The second way was more subjective. Every morning when I woke up, I'd do a self-test before getting out of bed. Move the left foot to the left, then to the right. Get out of bed, then walk a few steps. Note what's different. This was part of my ongoing effort to avoid another fall. Every morning my left leg felt different than the morning before. It was less controllable, and also seemed to be giving back variable resistance. What I was feeling was far outside the range of normal experience, which makes it hard to describe. Eventually, I gave up and just started calling it "squirreliness."

Based on the rate of change I was experiencing, I estimated that within three months I'd be unable to walk at all. Adding to my distress was the question of what was causing all of this in first place.

In late March, a team of neurosurgeons had removed a tennis ball-sized tumor from my right parietal lobe. The operation was a success in that everything that could be removed had been removed, and then some. But there are no "clean margins" in glioblastoma like there are in many cancers. There's always something left after surgery, primed to grow.

In mid-April, I'd undergone a brain MRI in preparation for chemoradiotherapy. Two members of my treatment team separately reported their conclusions, which were diametrically opposite. Dr. Staff Surgeon said that the tumor had regrown and that its rapid recurrence put it in the top 10% of cases they'd seen. Dr. Neuro-Oncologist said that MRI pointed to expected "blood products." There was nothing to worrry about. A tumor board agreed with Dr. Neuro-Oncologist, and Dr. Staff Surgeon changed their interpretation. Dr. Staff Surgeon explained that MRIs were sometimes hard to interpret.

This left me on edge for two reasons. First, if tumor growth were off the table, there was little else that could explain my worsening symptoms. Second, the most important diagnostic and prognostic tool for glioblastoma is MRI. It's not even close. Yet I'd just witnessed a first-hand demonstration of the technique's limitations.

My symptoms would continue to get worse right through chemoradiotherapy. They ebbed and flowed, but the overall downward trajectory remained constant. At one point I'd been prescribed a drug to help control brain swelling, which I'll discuss at some length in a later post. It relieved the symptoms for the first day, but less so every day thereafter until eventually it had no effect despite dose escalation. Almost every day I woke up to some new, bizarre left-side behavior that I'd somehow have to compensate for.

On May 13, I underwent a brain MRI. It showed something, at least according to the radiologist impression. An "impression" is a short text summary of findings from the MRI study. It's written by a radiologist, a specialist who looks at and interprets MRIs for a living. The report included several conclusions, including this one:

… persistent masslike T2/FLAIR signal within the splenium of the corpus callosum … concerning for residual nonenhancing tumor.

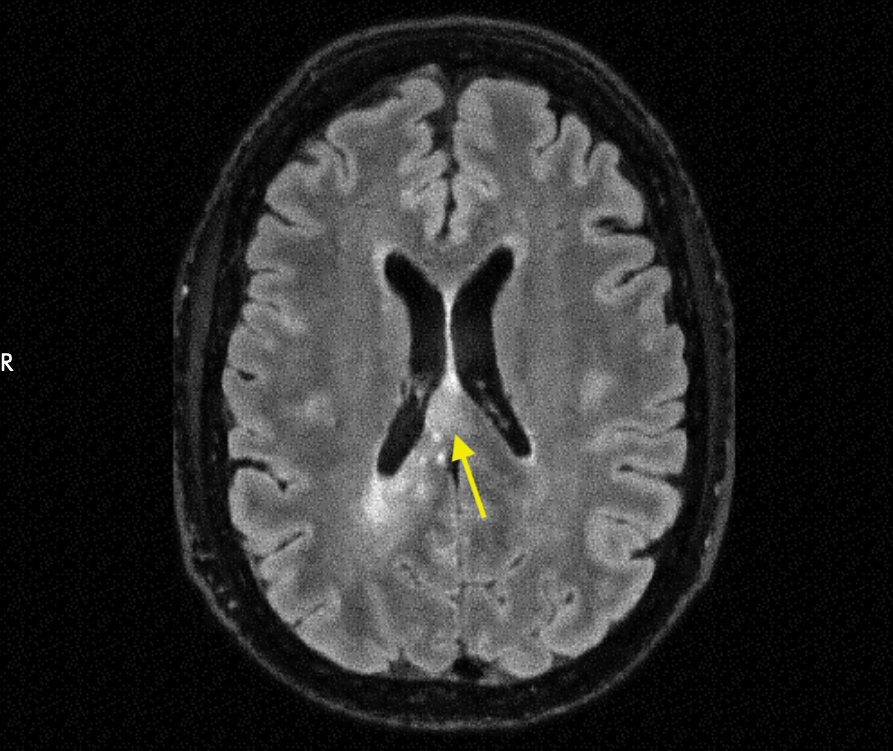

Below is an image from the study. The corpus callusum is a dense bundle of neurons running along the middle-top of the brain. The "splenium" is the round button-like mass that terminates the corpus callosum toward the back of the head (posterior). The splenium is considered off-limits for surgical purposes, which explains why residual tumor might be present there now.

"T2/FLAIR" is a mode ("pulse sequence") used during an MRI study. There are several MRI pulse sequences, which tend to vary based on the kind of tissue or fluid they enhance or suppress. T2/FLAIR is a pulse sequence that's used on brain cancer patients because its signal is thought to arise from tumor tissue. A bright spot on a T2/FLAIR MRI suggests the presence of tumor. T2/FLAIR "signal" shows up on an MRI image as brightness against a darker background.

T2/FLAIR responds to tumor, but not specifically. This is why the impression uses the phrase "concerning for," rather than less equivocal language. It's possible that brightness on a T2/FLAIR image results from either tumor or a few other things. This nuance was, in part, the source of the disagreement between Drs. Staff Surgeon and Neuro-Oncologist back in April.

I met with Drs. Neuro-Oncologist and Radiation Oncologist to discuss the latest MRI. Both disregarded the radiologist finding, attributing the T2/FLAIR signal to treatment-induced "swelling." This word (or the more technical term "edema") would be used repeatedly to dismiss the concerns raised by the radiologists.

On July 6, I underwent another brain MRI. Once again, it showed something of concern. The impression notes:

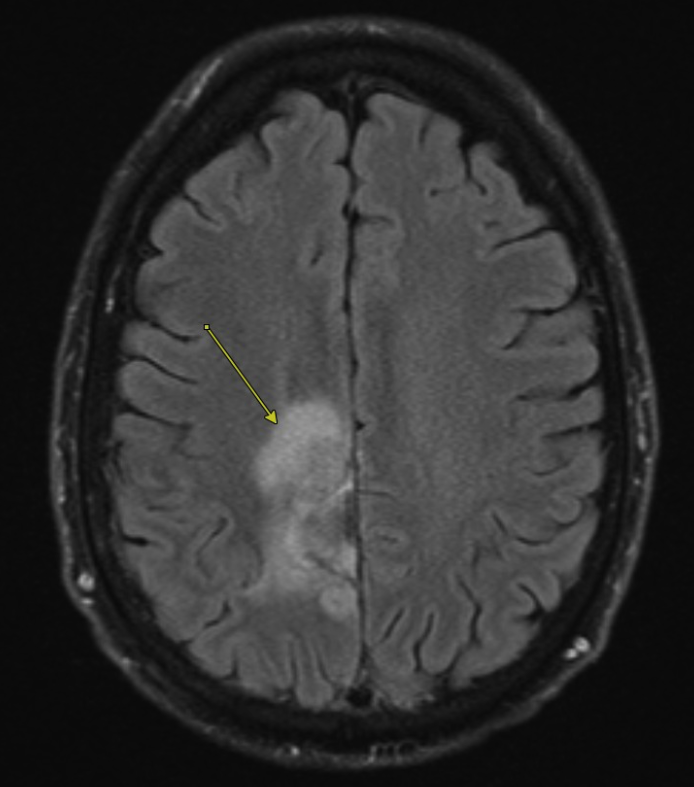

Compared to 5/13/2023, progressive masslike T2-hyperintensity along the right cingulate gyrus, anterior to the parietal resection margin is concerning for progressive nonenhancing tumor … . Persistent masslike T2-hyperintensity posterior to the resection cavity, visible on the same image remains concerning for residual nonenhancing tumor.

The comparison image shows a different slice depth, but the observation remained. Just to the left of center is a bright spot that is "concerning" for tumor.

Once again I met with Drs. Neuro-Oncologist and Radiation Oncologist. Once again these doctors dismissed the radiologist's concerns as treatment-related swelling.

As my symptoms progressed, I became more concerned. For some reason, both doctors were dismissing the radiologist's finding of possible tumor growth despite clear evidence of symptom progression.

On August 22, I underwent yet another brain MRI. This one was far enough after the end of chemoradiotherapy that treatment-related swelling would not fly as an explanation for T2/FLAIR signal. The impression notes:

Progressive interval increase in FLAIR signal hyperintensity within the cingulate and precentral gyrus of which at least some is masslike in appearance; however, the previously noted area of masslike FLAIR signal hyperintensity is changed in configuration due to progressive collapse of the resection cavity. Additional areas of masslike FLAIR hyperintensity within the posterior corpus callosum and anterior margin of the resection cavity appear less conspicuous on today's exam. Enhancement surrounding the resection cavity appears similar to prior albeit slightly decreased along the anterior margin with concomitant decrease in CBF in this area compared to examination performed in May.

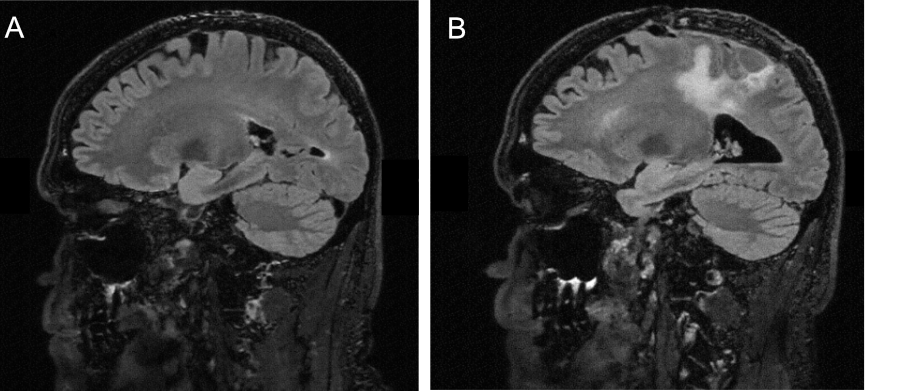

Unfortunately, several changes from July 6 to August 22 acquisitions make direct comparisons difficult. Instead, I'll show a side ("sagital") view with a 1:1 comparison to the April 15 MRI. This comparison shows progression of a T2/FLAIR hyperintensity, which appears to be growing along the top of my brain toward the front.

The new masslike T2/FLAIR signal runs roughly from the middle of my brain to the back for a few centimeters. The region toward the front of my head is the motor cortex, and the region toward the rear is the splenium of the corpus callosum.

The region that the masslike signal is growing toward is the motor cortex. As Wikipedia explains, the motor cortex:

… is the region of the cerebral cortex involved in the planning, control, and execution of voluntary movements. The motor cortex is an area of the frontal lobe located in the posterior precentral gyrus immediately anterior to the central sulcus.

The progression of my left-side symptoms is, and always has been, consistent with tumor growing into the motor cortex. The most recent MRI was the nail in the coffin for the edema hypothesis.

In our clinic appointment shortly after the MRI, Dr. Neuro-Oncologist acknowledged what multiple radiologists and my symptom progression had been saying for months, and which they had disregarded as swelling: the tumor was growing.

I suspected that the anterior part of my original tumor was left intact during surgery due to its nearness to the motor cortex. This part of the brain is resected very cautiously if at all due to the risk of causing permanent disability. The tumor that was left behind grew and was now infiltrating the right half of my motor cortex, thus causing my left-hand symptoms.

At the start of chemoradiotherapy, Dr. Radiation Oncologist had explained that my tumor would not be "melted away." At best, a successful treatment would prevent new tumor growth. Yet even this low low bar had not been cleared. The tumor had shrugged off the best therapy that modern medicine could muster without so much as a pause. Chemoradiotherapy had failed.