Dichloroacetate

As the end of chemoradiation therapy drew near, I considered next steps. In March I'd been diagnosed with a tennis ball-sized malignant brain tumor. The condition, glioblastoma, is incurable and universally fatal. The tumor had been surgically removed, but was bound to come back. Before it killed me over the next year or so, glioblastoma would inflict untold misery not just on me, but the people I cared about. They would watch me die piecemeal, one wretched symptom heaped onto the last, until my humanity was obliterated.

Most hospitals, including mine, paused treatments at the end of chemoradiation therapy, allowing patients to recover from the side-effects. After six weeks, the plan was to begin adjuvant temozolamide treatment, an idea that seemed insane to me on face value. The main problem was that my tumor lacked the characteristics needed for effective temozolomide treatment. I had grown increasingly hostile to the standard of care and its continued use after decades of abject failure.

I looked into every ongoing clinical trial but found most uninspiring. Many demanded way too much of patients while offering almost nothing in return, began with questionable scientific premises, or just mindlessly turned the crank on things that had been tried before and failed.

The landscape of second-line treatments looked equally bleak.

Opting Out of the Waiting Game

Just sitting on my hands waiting for recurrence seemed stupid and defeatist. I knew this thing would kill me given half a chance. Wasn't there something I could do in the meantime?

I turned to my scientific training, which said that when you reach a dead end in research, review the literature again because you may have missed something. I suspected that options to treat my condition had been reported, but my medical team would never even present them to me due to lack of US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) endorsement.

I was not wandering the literature aimlessly, but rather looking for something very specific. I pulled every paper I could find in which a small-molecule drug had been administered to humans and had shown even the slightest hint of altering the course of disease progression. (I consider a "small molecule" to have a molecular weight under around 600 g/mol, or roughly 30 non-hydrogen atoms).

Of the small molecules that had been tried in humans, I only considered those with good oral bioavailability. I had no interest in intraveneous (IV) dosing. The drug also needed either demonstrated brain permeability (the ability to cross the "blood-brain barrier") or the potential for it based on structure as judged by me. One of the problems that has plagued glioblastoma drugs is the need to cross the blood-brain barrier. A lot of highly speculative approaches had been tried to get drugs without this property into the brain anyway. I thought they all were dead ends.

Qualifications

What follows will be a highly technical discussion. It's fair to ask what qualifications I have to do this, especially given the depressingly large amount of bad medical information on the Internet.

I earned a Ph.D. in organic chemistry from the University of Texas at Austin after earning a B.S. degree in chemistry from U.C. Berkeley. During my doctoral and later postdoctoral research at Stanford I designed, synthesized, characterized, and tested small-molecule catalysts. After my studies, I worked as a medicinal chemist for a large pharmaceutical company.

My job as a medicinal chemist was to design and synthesize small molecules with the ultimate goal of treating brain disorders. I worked as part of a team of highly-trained chemists and biologists. In a nutshell, I decided what compounds to make (most had never been reported in the literature before), figured out how to make them, made them (or worked with other chemists to make them), gave these compounds to a member of the biology team to be tested (typically in cell preparations or rats), and then helped interpret the results. Having done that job for eight years on a few projects, I'm comfortable working with a wide range of chemical and biological data. I've co-authored several patents and papers on investigational drugs.

More information is available in my bio.

A Lead

My search of the literature uncovered several leads, but one by Michelakis et al. from 2010 immediately jumped out: Metabolic Modulation of Glioblastoma with Dichloroacetate. Dichloroacetate (aka "sodium dichloroacetate," "dichloroacetic acid"), is structurally related to vinegar. It's a small, simple molecule, features I'd found time and again to be extremely helpful in my medicinal chemistry work.

The paper presents several lines of evidence consistent with dichloroacetate's ability to slow or even reverse the growth of glioblastoma. The proposed molecular basis for the therapeutic effect is fascinating, but far too involved to get into here. Suffice it to say that cancer cells metabolize glucose uniquely, which endows tumors with some important advantages. Dichloroacetate disrupts this abnormal glucose metabolism, eliminating the advantages, and leaving cancer cells vulnerable to death. At the same time, dichloroacetate has little to no effect on non-cancerous cells.

Unfortunately, the clinical work suffers from two technical problems, which I suspect have dampened interest in this paper over the last thirteen years. First, only five patients were included, which is few even by glioblastoma standards. Second, no two patients were treated in exactly the same way, which makes it very difficult to draw conclusions. This experimental irregularity makes the clinical work look more like a collection of individual case studies than a clinical trial. The irregularity is most apparent in the paper's Supplementary Materials. I'm not trying to find fault with the authors, who were clearly working under extremely challenging conditions, but rather to point out the difficulty in interpretation.

With that caveat, I'll do my best to summarize what was reported. Let's start with the case studies.

Case Studies

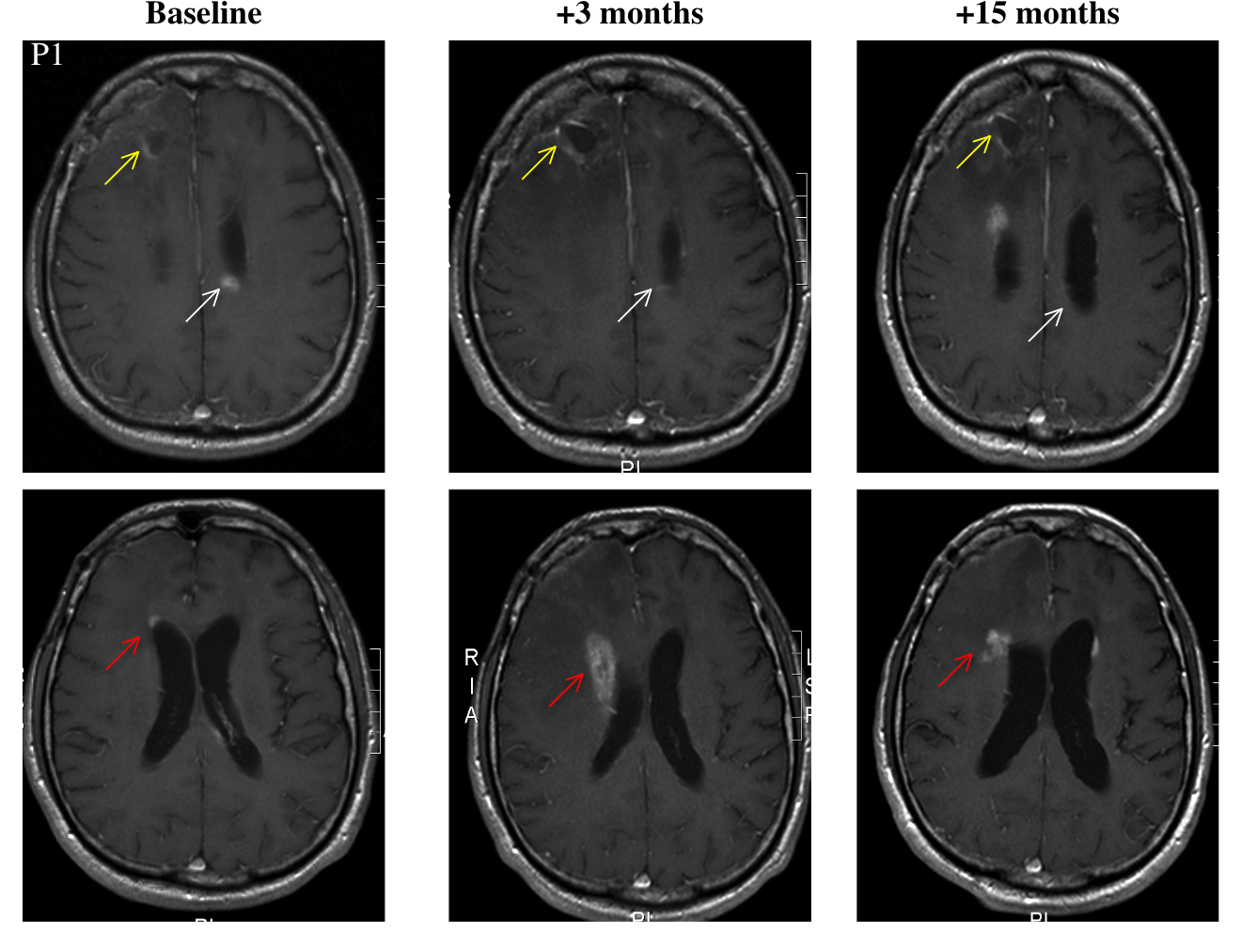

Patient 1 is 58 year-old male who received "standard therapy" (presumably maximum safe resection followed by temozolomide-chemoradiation). Four months after the end of chemoradiation, the patient's tumor started to grow. He then started taking DCA.

The timeline of Patient 1's treatments is reported in an unclear way. The best that I can surmise is that progression occurred 13 months after surgery at which point DCA administration started. DCA was then continued for 15 months. At the end of this period, the patient's disease was clinically stable. An MRI study showed no growth at the primary tumor site and "significant regression" at two secondary sites.

Patient 2 is a 47 year-old female who was treated with surgery, radiation, and temozolomide. It's unclear whether these later two were administered simultaneously. Progression occurred in several episodes, which were treated with a variety of drugs. She underwent multiple debulking surgeries. Following her last surgery, she started taking DCA. At "month 11," (reference point not given) she underwent another surgery to drain a cyst. Fifteen months after the start of DCA, the patient was clinically stable, and an MRI study showed "sustained" improvement.

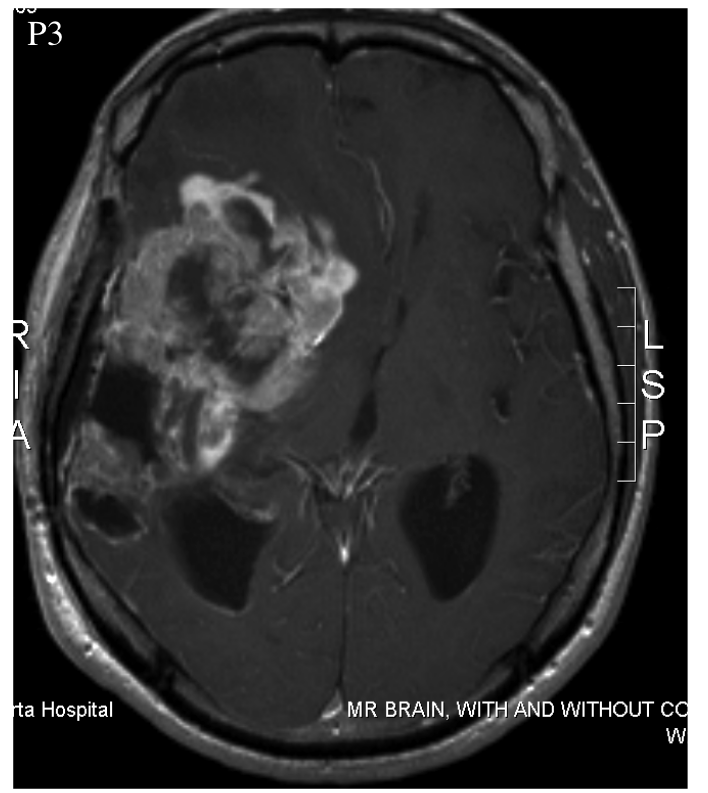

Patient 3 was a 52 year-old male who was treated with surgery, radiation, and temozolomide. It's unclear whether the latter two were administered simultaneously or not. Multiple progressions occurred, which were treated with a variety of drugs. At least one additional surgery was also performed. The patient experienced an inoperable progression, leaving him with clinical impairment. At this point, the patient began taking DCA. Elevated fluid pressure within the skull caused his death three months later.

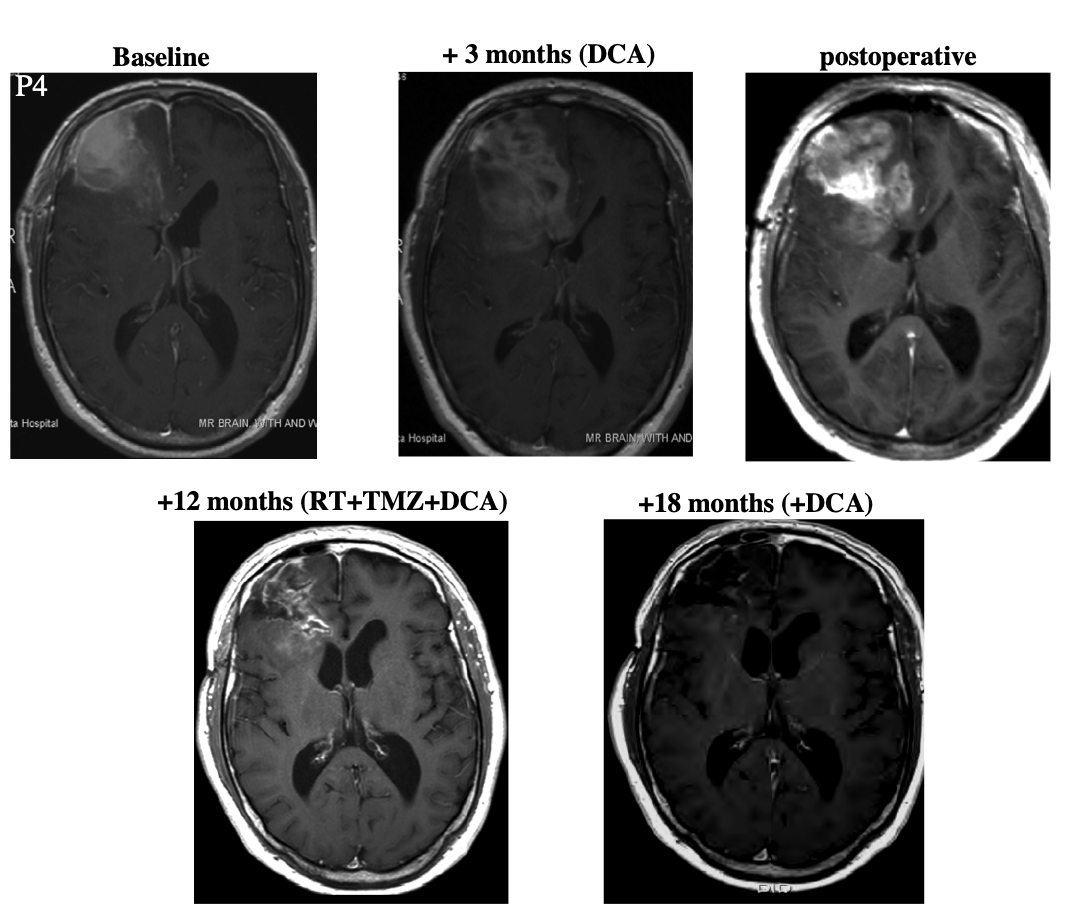

Patient 4 was a 45 year-old male who underwent resection. At some point after this, he began taking DCA. After three months, the patient began "standard therapy" (presumably concomitant radiation and temozolomide) while continuing to take DCA. Three months later, he showed "radiologic evidence of disease progression." After a second debulking surgery, he continued taking DCA together with the "standard therapy (radiation and temozolomide)." Because the patient showed "ongoing regression," temozolomide treatment was continued for a total of nine months. Then the patient continued taking DCA alone for six months. At this point the patient was asymptomatic and MRI showed no progression.

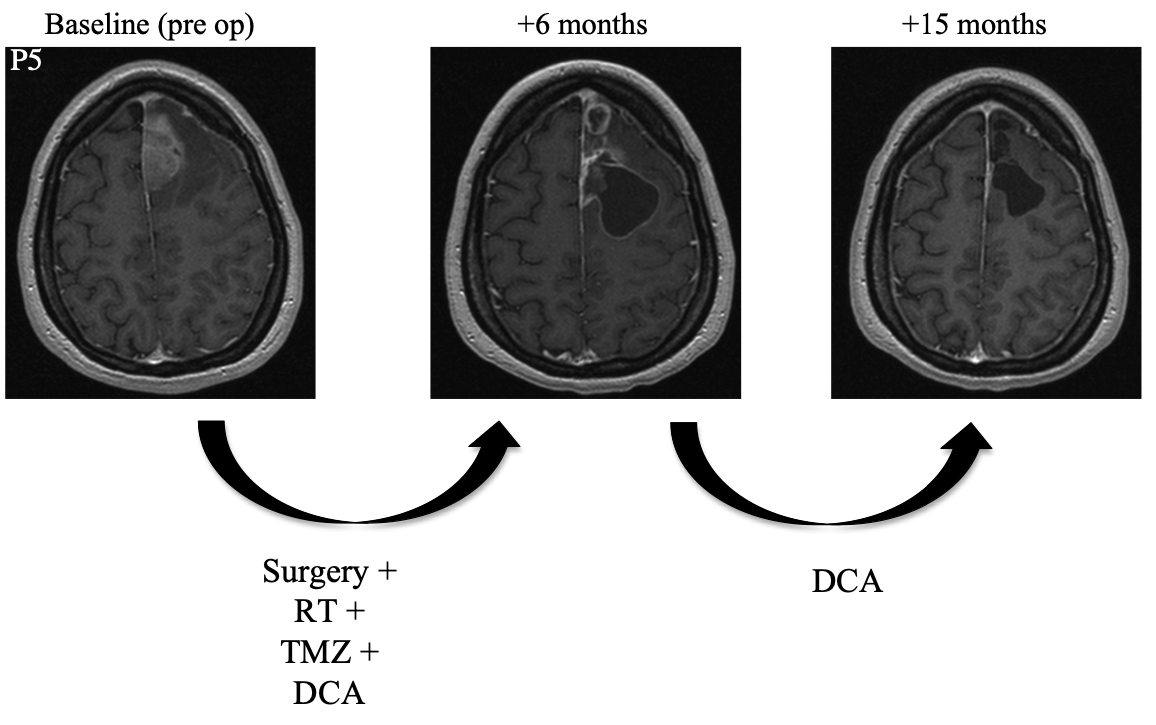

Patient 5 was a 30 year-old female who underwent resection. She then began a combined regimen of radiotherapy, DCA, and temozolomide. Radiotherapy was administered for an unspecified amount of time. Temozolomide was administered for a total of six months. DCA was administered for a total of fifteen months. At follow-up fifteen months after surgery, MRI showed complete resolution of the tumor and the patient was symptom-free.

Dosing

Patients were dosed orally using a solution prepared from solid DCA dissolved in 20-30 cc of water. Patients drank the resulting solution once every twelve hours "on an empty stomach."

Each patient received one of the following DCA doses: 6.25 mg/kg; 12.5 mg/kg; or 25 mg/kg. The dose was escalated or de-escalated based the patient's ability to tolerate the drug's main side-effect: peripheral neuropathy, which may manifest in a number of ways including numbness, burning, or tingling among others. All patients started at 6.25 mg/kg, staying with that dose for at least three months.

Pharmacokinetics

Within the first three months of DCA administration, serum trough concentrations of the drug were "undetectable." However, after three months at the 6.25 mg/kg dose, the serum concentration of DCA ranged from 394 to 426 mM, remaining at around that level for many months. A similar induction period and trough concentration after it was observed in previous clinical work with DCA. The effect appears to be due to DCA acting as an inhibitor of the enzyme primarily responsible for its metabolism.

Ex Vivo

Bain tissue samples were collected from Patients 2, 3, and 4, both prior to and after DCA treatment. Among the observations made by comparing pretreatment and posttreatment samples were:

- lower cell density

- lower cell proliferation

- increased apoptosis

- increased activity of the enzyme pyruvate dehydrogenase, consistent with the hypothesized molecular mechanism of action

Follow-Up

The paper has been cited over 800 times according to Google Scholar. Most of these citations appear to come from general reviews or papers discussing DCA in the broader context of cancer chemotherapy.

However a few studies have attempted to build on the work of Michelakis et al. Some of the more interesting of these include:

- Phase 1 trial of dichloroacetate (DCA) in adults with recurrent malignant brain tumors. Finds that oral DCA was well-tolerated.

- A phase I open-labeled, single-arm, dose-escalation, study of dichloroacetate (DCA) in patients with advanced solid tumors. Reports side effects including nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

- Sensitization of Glioblastoma Cells to Irradiation by Modulating the Glucose Metabolism. An in vitro study showing synergy between DCA and radiation treatment.

- Effects of dichloroacetate as single agent or in combination with GW6471 and metformin in paraganglioma cells. In vitro study that showing some efficacy.

- Dual-targeting of aberrant glucose metabolism in glioblastoma. In vitro study shows efficacy of DCA/phenylarsenous acid combination.

- Dichloroacetate reverses the hypoxic adaptation to bevacizumab and enhances its antitumor effects in mouse xenografts. In vivo efficacy of DCA-Avastin combination.

- Dichloroacetate induced intracellular acidification in glioblastoma: in vivo detection using AACID-CEST MRI at 9.4 Tesla. Application of one of DCA's effects for diagnostic purposes.

- Case Report: Sodium dichloroacetate (DCA) inhibition of the “Warburg Effect” in a human cancer patient: complete response in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma after disease progression with rituximab-CHOP. Case reports of patents self-reporting the use of DCA to treat cancer found through internet forums. One patient demonstrated complete remission, albeit not of glioblastoma.

- Antitumor activity of dichloroacetate on C6 glioma cell: in vitro and in vivo evaluation.

- DCA promotes progression of neuroblastoma tumors in nude mice. C6 is an animal model for glioblastoma, and DCA's activity toward it suggests a possible route toward animal studies of DCA's in vivo activity.

- PP2A-based triple-strike therapy overcomes mitochondrial apoptosis resistance in brain cancer cells. In vivo and in vitro studies aimed at using DCA as part of a combination therapy to target mitochondrial behavior in cancer.

- Synergistic effect of dichloroacetate on talaporfin sodium-based photodynamic therapy on U251 human astrocytoma cells. In vitro study suggesting that DCA can be used in combination therapy.

- Trial of Dichloroacetate (DCA) in Glioblastoma Multiforme (GBM). Ongoing trial with 40 patients for pre-surgical DCA treatment.

- Repurposing phenformin for the targeting of glioma stem cells and the treatment of glioblastoma. In vitro study of temozolomide/DCA combination therapy.

Caution

Dichloroacetate appears to have few known side effects aside from the well-known potential for peripheral neuropathy. I did, however, find a handful of reports indicating the potential for other problems. One of them is contained in Severe encephalopathy and polyneuropathy induced by dichloroacetate.

The case study reports on a 46 year-old melanoma patient who presented with confusion and unsteady gait. Four weeks previously, the patient had started taking capsules labeled as DCA at a putative dose of 15 mg/kg/day together with vitamin A capsules. Impaired mental ability and dysarthria (difficulty speaking) were also observed. For unexplained reasons, the patient was treated with the antipsychotic haloperiddol and the anxiolytic lorazepam.

For unknown reasons, the team treating this patient decided to draw a sample of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). DCA was found there at a concentration 78 μg/mL, which they report is even higher than the average maximal plasma concentration of 53 μg/mL in adults undergoing long-term DCA therapy. Inexplicably, the patient's plasma concentration of DCA was not reported. To my knowledge, this is the first and only measurement of CSF DCA concentration in humans. Taken together with other reports, this suggests that orally-dosed DCA could gain broad exposure to the brain and spinal chord.

After two days some of the symptoms resolved. Neither CSF nor plasma DCA concentrations at that point were reported.

The authors conclude that it was likely that "DCA accumulation occurred in our patient." They also speculate that this accumulation may have been aided by the high dose of vitamin A taken together with the DCA. They conclude with the cautionary message "… we strongly advise the use of DCA in clinical trials only."

I found several case reports of DCA self-administration and may summarize them in a separate article. The point I wanted to make here is that DCA has not been studied much in humans and that taking it carries many serious risks.