Just Saying "No" to Adjuvant Temozolomide

The end of chemoradiotherapy in early June was an important milestone for me. In late March I'd been diagnosed with a tennis ball-sized malignant brain tumor, a terminal condition known as glioblastoma. Since diagnosis, most treatment decisions had been automatic because my doctors were following the "Standard of Care" (SoC). This consisted of, first, surgery to remove and characterize the mass. The surgical site was then irradiated with X-ray radiation over the course of 30 weekday sessions. At the same time I'd taken daily oral doses of the non-selective DNA alkylating agent temozolomide (aka "Temodar" or "TMZ"). The completion of this bimodal treatment, known as the "concomitant" phase, is an important time in the life of every glioblastoma patient. Before this point, the SoC dictates treatment decisions. But the last dose of radiation marks the beginning of something new. For the first time, doctors and patients face a wide range of choices that were not previously on the table.

One decision is the length of "adjuvant" treatment. This is the period following radiotherapy during which temozolomide is administered on a twenty-eight day cycle. Over the first five days, temozolomide is taken at a dose about three times of that taken during radiotherapy. For the next 23 days, no temozolomide is taken. At least six such cycles is the goal. However, patients may complete more or fewer cycles, with side-effect tolerance often playing a deciding role.

During chemoradiotherapy I'd made a worrisome discovery: I would derive almost no benefit from the temozolomide I'd taken. The reason was that my tumor's promoter was "unmethylated". Glioblastomas carry a gene encoding the DNA-repair enzyme MGMT. This enzyme reverses the chemical DNA modification performed by temozolomide. Lack of promoter methylation meant that my tumor expressed MGMT at full strength, rendering alkylating agents like temozolomide ineffective.

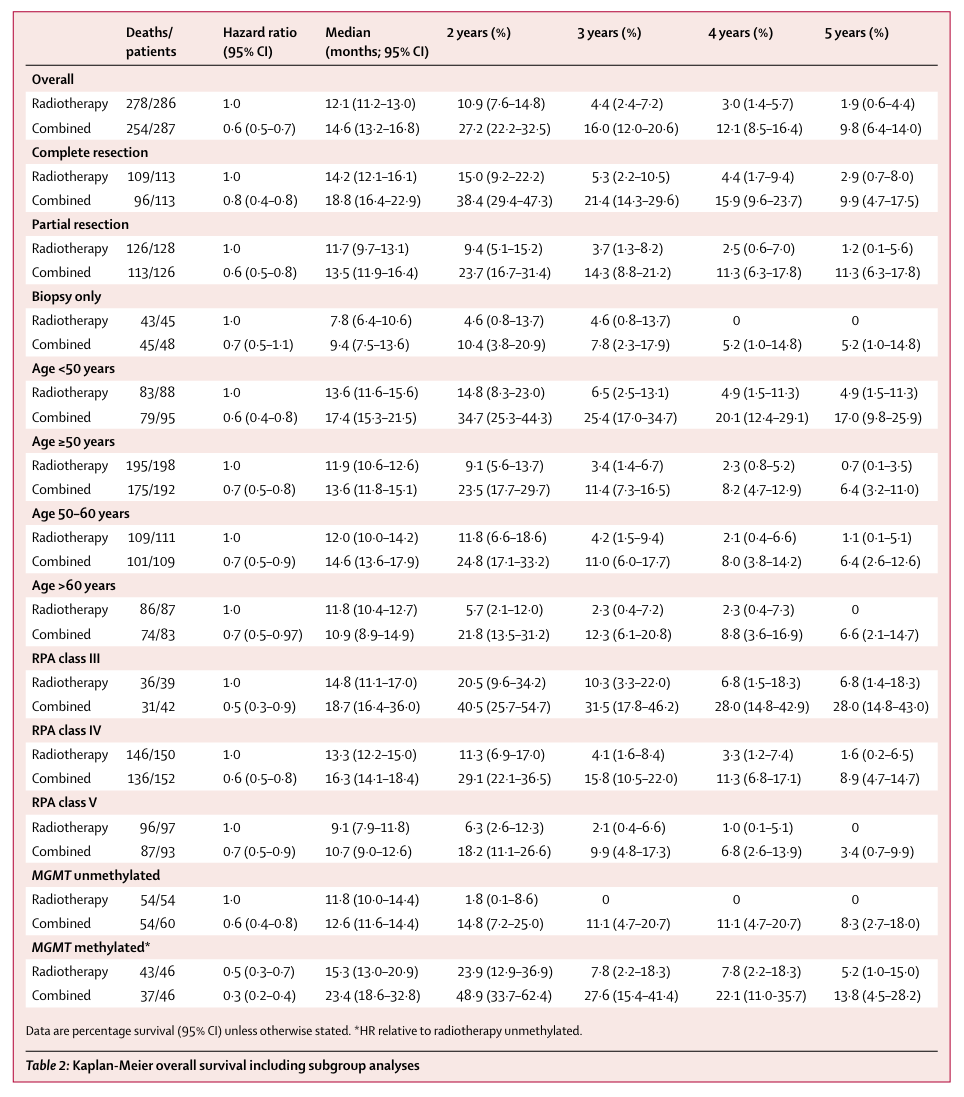

This was no academic exercise. Lack of MGMT methylation translates clinically into worse prognosis (Figure 1). Median survival for MGMT unmethylated patients on the standard of care (12.6 months) was about half of the median survival for MGMT methylated patients (23.4 months). More to the point, patients with unmethylated tumors had a median survival of 11.8 months when temozolomide was omitted from the SoC whereas patients who augmented radiotherapy with temozolomide had a median survival of 12.6 months. In these patients, the chemotherapy part of the standard of care accomplished almost nothing.

This split in patient response becomes even more striking when one considers that about half of glioblastoma patients have tumors whose MGMT promotor is unmethylated. As I've noted before, I was a member of this unlucky club.

If temodar were free of side-effects, this situation might be tolerable. Unfortunately, temodar comes with a rather lengthy list of known side effects, including these common ones:

- headache, seizure

- constipation, nausea, vomiting diaarrhea, belly pain, loss of appetite

- trouble with memory

- difficulty sleeping

- muscle weakness, paralysis, difficulty walking

- dizziness

- tiredness

Because of these side-effects, one does not simply take temodar. There's another drug to control nausea (e.g., ondansetron). There's another to counter constipation (e.g., miralax). Specific underlying conditions may require additional medications. It's unclear how many instances of memory loss, seizure, muscle weakness, and fatigue reported by glioblastoma patients were actually caused by temozolomide or a member of its entourage.

Perhaps the most concerning side-effect of temozolomide is one that isn't felt directly: immune suppression. Temozolomide blocks the production of both red and white blood cells, which is why patients need to be closely monitored. In severe cases, immune suppression can manifest as irreversible bone marrow damage. Given the current intense interest in immune therapy for glioblastoma, the near-universal prescription of an immune suppressor to patients seems counterproductive at best.

To mitigate the effects of immune suppression, a prophylactic antibiotic is prescribed together with temozolomide. This drug combination is mandatory during chemoradiation therapy, and strongly encouraged during the maintenance phase.

It would be one thing if the temozolomide drug cocktail resulted in a marked improvement in median survival. But for patients with unmethylated tumors, the reward is small. Recognizing this, no lesser authority than Stupp himself has noted:

Together, the data allow the conclusion that alkylating agent chemotherapy is of marginal benefit, if any, for patients with MGMT unmethylated GBM. … By continuing to treat the majority of MGMT unmethylated patients with TMZ, we are missing an opportunity to do better. Innovative treatment approaches with novel agents in combination with RT may provide a better chance for improved outcome than adhering to the use of an agent with marginal activity. From the patient’s point of view, it may be perceived as "wasting the last opportunity" to try a potentially efficacious new agent. Clearly, this patient population would benefit most from drugs with other mechanisms of action. To date, only a few trials have selected patients and assigned treatments according to MGMT promoter methylation status.

I'm disturbed that a drug with clinically demonstrated lack of efficacy and a notable side-effect profile continues to be prescribed to roughly half of the glioblastoma patient population. It raises important questions that I think should be answered.

Alarmed at what I'd found, I brought the published clinical data to the attention of Dr. Neuro-Oncologist. Or more precisely, they brought the study to my attention after I asked about MGMT methylation, believing it to demonstrate a benefit. It didn't take long with a copy of the paper to find the relevant information clearly showing temozolomide's lack of efficacy for patients like me.

"Don't the available data suggest that patients with unmethylated tumors such as myself should not be prescribed temozolomide?" I asked Dr. Neuro-Oncologist.

"What I can say is that temozolomide was prescribed to all patients at every institution at which I've served," Dr. Neuro-Oncologist said. They then listed the names of these well-known and highly-respected institutions.

From my perspective, the clinical data are all that matters. And the data make it clear that temodar is at best marginally effective for the half of glioblastoma patients lacking MGMT methylation.

A doctor prescribing any medication has the obligation to convince patients of the drug's usefulness. If that can't be done, it may point to an opportunity for medicine to, as Dr. Stupp suggests, "do better." I believe doctors should jump at the chance, but this does not appear to have happened in the many years since the facts about temozolomide and MGMT methylation have been known.

I now believe that doctors who take the same approach as Dr. Neuro-Oncologist are doing a disservice to their patients and to the entire field. Despite large expenditures of resources over the decades, the prognosis for glioblastoma patients has barely budged. I suspect that part of the problem is that doctors today are being swayed by factors other than data.

Rather than level with the half of the glioblastoma patient population that will get nothing but side-effects from temozolomide, saying "There is no chemotherapy that has been proven effective for you, and so I can prescribe none," doctors continue to tell patients half-truths like "All patients derive some benefit from temozolomide, but those with methylated tumors derive the most." If you squint really hard, such a statement might be justified. But when patients ask doctors what to do to get better, I think they assume the field will be surveyed with both eyes wide open. At least I did.

I refuse on principle to take any medication that has been clinically demonstrated as ineffective. A pill with nothing but side-effects may satisfy desperate demands from dying patients to "do something," but does little to treat the disease, serve the patient in any meaningful way, or move this languishing field of medicine forward. My shipment of temozolomide arrived for my adjuvant therapy, but I have not and do not plan to take it.